ABOUT

- Learn all about the new trends in the energy market and its evolution in the near future in an extensive and well-documented article by Marian Pilescu

INTERVIEW

1. Energy means a lot

Energy is the cornerstone of our civilization’s progress, and our modern way of life owes much to it. We rely on energy to produce and consume almost everything, from household appliances to transportation, and from industrial processes to agricultural practices.

In Europe and America, the entire economic system is based on energy consumption and the sources we use to produce it generates emissions at a high pace, but they come with some advantages as the energy output is high, it’s easy to produce and at the moment we have enough of fossil fuels.

While fossil fuels offer several advantages, such as high energy output and ease of production, the negative facts associated with their use are becoming more evident. In 2022, the coal still represents the main energy source for Czech Republic, Estonia, Ukraine, Poland and Bulgaria – coal produces more emissions than any other energy resource.

The energy is not limited to electricity consumed in households, it also includes heating, transportation, raw materials for production, and agricultural inputs, such as chemicals.

All in all, everything we utilize, even the packing of food, is made with the help of energy.

Although is clear that energy production generates pollution and diseases causing deaths, we can’t simply stop producing given our dependence on it.

The first time the term energy transition was coined in media and among politicians was after first oil crisis is the ’70, but since then the pollution caused by fossil fuels only increased.

However, the new EU directives seems to push more on energy producers and the new initiatives while setting real targets for future decades.

Although the final aim is to reach carbon neutrality, not an easy target, at least, we witness real improvements in energy sector investments towards green and sustainable methods of production.

2. European Renewable Energy Directive (RED)

Several EU initiatives aim to achieve a climate-neutral environment by 2050.

To understand the context we shall go back in time to one of the first important steps which set the fundamental ideas for energy transition: the Kyoto Deal in 1997 where after many years or ideas, commitment and individual actions made without a common approach the countries with the biggest greenhouse emissions share have set a deal to decrease their pollution.

The deal was signed by US, Canada, EU, Russia, Japan and Australia. The effect of this deal was not as expected, even though Europe decreased its emission with a fair share of around 20% in the next 15-20 years, some may argue this was achieved by relocation of production outside its borders.

Despite the challenges, the Kyoto Deal was a significant milestone in global efforts to address climate change. It paved the way for further international agreements and initiatives, such as the Paris Agreement in 2015 and the EU’s ambitious targets for carbon neutrality.

The EU began to take the issue of renewable energy and climate change more seriously with the introduction of the first European Renewable Energy Directive (RED) in 2009.

This directive set national renewable energy targets that were expected to be achieved by 2020, with an overall 20% target at the EU level.

The plan was elaborated setting different targets for different countries taking into consideration the starting point and the future potential – the boundaries were set by Malta with a 10% target and by Sweden with 49%.

In 2016, the European Commission released an initiative called “Clean Energy for all Europeans”, which led to the recasting of the initial RED deal and established new targets for the future.

One of these targets was to achieve a 32% renewable energy share by 2030. This was a significant increase from the 20% target set in the initial RED deal.

The 2018 revision of RED introduces also a new section in respect with various sectors which are slowing down the process – heating, colling and transportation, for example a target of 14% of share for renewable fuels in transport by 2030.

Further revisions of this directive pushed even more optimistic targets. However, this directive moved the old fashioned fossil fuel focus of energy in EU to future renewable and sustainable means of production.

A short timeline of investments which rises inside EU as a response to various initiatives:

- 2000: first large scale offshore wind farm in Denmark;

- 2008: Olmedilla Photovoltaic Park in Spain – largest power plant in the world – generates electricity for 40 000 homes / year;

- 2014: offshore wind is cheaper than coal, gas and nuclear – first time in Europe – after various investments in the North Sea ;

- 2019: EU power production from wind and solar exceed coal for the first time.

Fig 1: Renewables Energy Milestones in Europe Source: commission.europa.eu

3. The European Green Deal (EGD)

European Green Deal introduced in 2019 sets up a long term strategy and a roadmap to achieve carbon neutrality and climate objectives by 2050 and make Europe the first climate neutral continent.

While RED was more focused on renewable energies, EGD comes up with a wider plan not only focused on a specific point but offering a general guideline. Energy is the main topic since it’s estimated that more than 75% of EU greenhouse gas emissions comes from this sector.

Focus areas are:

- Ensure a secure and affordable energy market with no net emissions;

- Promoting a common energy market, highly digitalized, in EU;

- Promoting energy efficiency.

The deal brought new guidelines in respect with the reduction of energy consumption by increasing energy performance of everyday products. This resulted in new energy standards on household products, the deal also promotes energy efficiency and eco-design of new products, common and integrated solutions, increase of modern public transportation infrastructure, longer lasting products that can be repaired.

Immediately after the launch of EGD in December 2019 the Covid-19 outbreak brought an economical decline over Europe slowing down the economy and pushing out green deal initiatives from the main agenda of European focus.

While everyone was still struggling to end the recession caused by the virus, Russia invaded Ukraine which brough new negative economic effects on the continent.

The new war in Europe adversely affected the energy transition on short term since EU was highly dependent on Russian fossil fuels to fulfill current day to day energy needs. As a fast response to the new crisis, EU policy makers will propose either a delay in EGD or lower of the initial targets.

The experience after Covid taught us that some actions taken under pressure on urgency without keeping a long term goal in mind is not necessary the best way to act.

A certain degree of preparedness for some countries demonstrates that reacting to crisis without a deep analysis can be costly. Maybe the war means we shall boost investments in green energy and increase pace in the transition.

In 2021, Europe imported from Russia around 40% of the total gas consumption and 46% of the total coal used to produce energy.

The sanctions imposed by EU to Russian raw materials made the prices of energy to rise like never before, while some production facilities in Europe choose either reduce the production or close some production lines either completely shut down the activity.

However, the EU bloc recognise the dependence on Russian fossil fuels as a security issue, bringing now the energy transition not only a climate oriented issue but also has put this topic on the security agenda.

4. What are the alternatives?

The energy transition is time consuming and quite costly; it can be achieved only through small steps. While EU invest in green sector, we must keep up to date the traditional energy facilities.

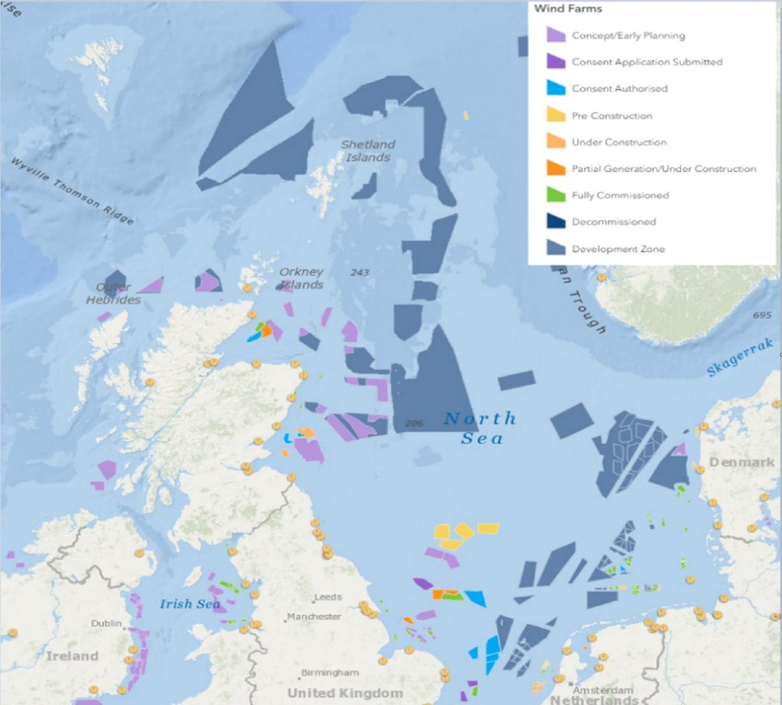

Multiple alternatives available in EU countries starting from utilizing the wind potential in the North Sea to the geothermal steam from Iceland. On short terms we must move from old fashion coal-based energy to natural gas. On shore wind energy represents an abundant resource waiting to be converted into energy.

More than 46 windfarms are located across North Sea operated by companies from Germany, UK, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark adding up to more than 2600 turbines.

More investments are already announced hence there will be a growth in this sector.

Fig. 2: Wind Potential in the North Sea Source: Sciencedirect.ro and TGS 4C Offshore

The energy crisis in 2022 has brough a series of investments on liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and vessels to replace Russian natural gas supply.

New pipelines are drawing new routes of LNG supply in Europe which is now the biggest importer of LNG. Year over year LNG imports from US has doubled and now Europe represents 50% from the total of US LNG exports.

Along with the terminals and vessels there were investments in LNG storage and capacity meet around 40% of total gas consumption.

The LNG terminals in Europe adds up to the following:

- 12 operational in Italy, Greece, Malta, France, Spain and Lithuania;

- 9 operational but also planned for expansion in France, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium and Poland;

- 2 under construction in Finland ;

- There are plans for another 12 LNG terminals in Greece, Italy, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Spain and Baltic Countries.

Fig. 3: LNG Terminals in EU Source: European Commission

Hydrogen plays a key role in achieving energy efficiency but at the moment it is used primarily in producing various goods such as plastics and fertilisers, creating a significant amount of CO2 emissions.

For the moment hydrogen is produced very close to the place of consumption but there are plans for producing it at a large scale and also to transport it locally as well as on long distances – EU through its commitments has a target of producing 10 million tones and import another 10 million by 2030. EU has developed a separate hydrogen production strategy with various detailed actions which emphasizes why hydrogen is an important element of local energy strategy.

Hydrogen can be produced through various processes, however some of them are high in CO2 emissions while there are others close to zero (or potential zero) therefore hydrogen production is categorised in the following categories:

- Brown Hydrogen – made with coal – producing highest greenhouse emissions but low in production cost;

- Grey Hydrogen – made with natural gas – high in emissions, but better than coal – as well, low in production cost;

- Blue Hydrogen – made with natural gas but utilising an advanced gas reforming methodology, low in emissions and 60% more expensive cost of production;

- Green Hydrogen – made through electrolysis from renewable energy, potential zero emissions but high in production cost up to 5 times more expensive than other methods.

The hydrogen is seen as the future of energy and during March 2023 EU Commission announced a so called “Hydrogen Bank” initiative to unlock private investments in hydrogen value chains, both domestically and in third countries, by connecting renewable energy supply to EU demand and addressing the initial investment challenges.

Many would argue there are too many specifics we don’t know about hydrogen and it is too early to assume we can safely produce it at a larger scale. While the natural gas pipelines have multiple leaks across their routes in Europe (in particular in Russia) this is not an option for hydrogen, if even 10% leaks during production, storage or transportation process it may become worse than fossil fuels for the environment.

It is believed that we must work on a better leakage detection technology and invest more in R&D before promoting hydrogen storage and transport.

While the alternatives mentioned earlier can address land-based energy transitions, an alternative for air transport is Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF).

SAF is very convenient as being a blend with possibility up to a 50% concentration with conventional jet fuel without requirement of any aircraft modifications. It can reduce as much as 80% of CO2 emissions generated by flights. SAF is not new and according to Shell it was used in 2008 and fast growing since then

There is a variety of technologies for SAF production, in the end this is just a blend for jet fuel, not replacing it completely.

The feedstock is composed on various mixtures of:

- Used fat, oil and grease;

- Municipal waste;

- Waste and residues from agriculture of forests.

SAF is becoming more and more popular with 300 million liters produced in 2022 and more than 450 000 flights conquered the skies using SAF between 2010 and 2023.

Airbus invested in research to push usage of SAF in higher shares with an aim of 100% usage by 2030.

European continent was again a pioneer in promoting SAF with the following regulations:

- National blend mandate promulgated in: France, UK, Norway and Sweden;

- National blend mandate under assessment: Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland and Turkey.

However the regulations refer to small amounts of SAF, a few percentages only as mandatory since the availability of production facilities and feedstock represent a problem. Currently the Norwegian government stipulated that the biomass to produce SAF shall come from waste and residues.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the European Union aims and targets are optimistic, most probably this is the perfect place on earth to start green initiatives. Regulations in place are well respected and Europe has the power to overcome economical difficulties and find the path to recession recovery. Green initiatives are still here, and targets are even more ambitious after all the new challenges faced since 2020 – Covid outbreak and Russian invasion of Ukraine. Energy transition is a very complex process and in hands of the same big energy suppliers under EU regulation. Furthermore, the transition will bring not only a clean environment but also more jobs, new industries and less dependency on others.